If you’ve ever asked students a question only to have tentative responses come back like “Yes… No… Uh… Yes…”, then you’ll enjoy this story.

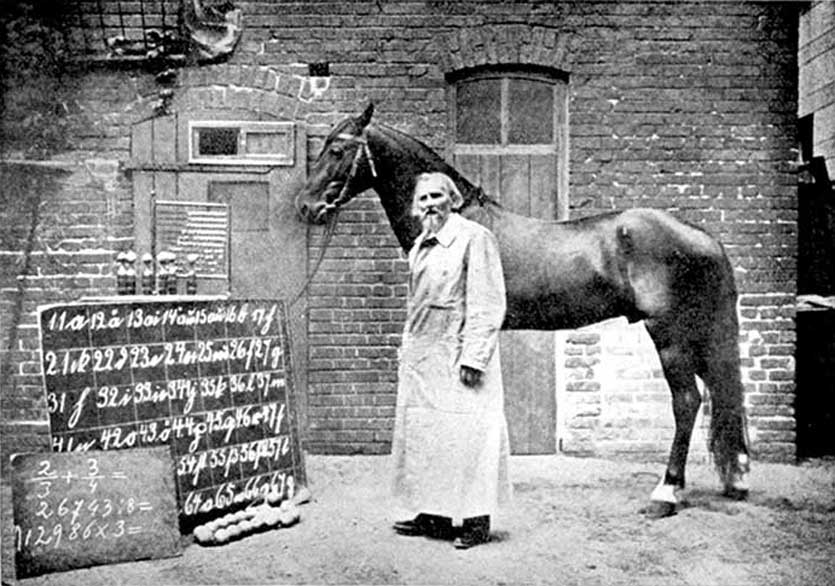

In the early 1900s, there was a famous horse named Clever Hans that amazed people because of his intelligence. At first Hans was able to count objects and then tap his hoof to state the number of objects. So, if he saw 4 objects, he would tap his hoof 4 times. Over time his owner Wilhelm von Osten was able to teach him how to add and subtract. Then he was taught to “multiply, divide, work with fractions, tell time, keep track of the calendar, differentiate musical tones, and read, spell, and understand German.”

This amazed audiences of people who came to observe this feat. Obviously, people suspected fraud, because how could a horse do something like this? Here’s what happened:

As a result of the large amount of public interest in Clever Hans, the German board of education appointed a commission to investigate von Osten’s scientific claims. Philosopher and psychologist Carl Stumpf formed a panel of 13 people, known as the Hans Commission. This commission consisted of a veterinarian, a circus manager, a Cavalry officer, a number of school teachers, and the director of the Berlin zoological gardens. This commission concluded in September 1904 that no tricks were involved in Hans’s performance.

They even ruled out fraud by writing the questions on paper, having someone else ask the questions, and removing von Osten from the room. For a while, no one could figure out how the horse was able to answer these questions.

Eventually the breakthrough came when they realized that Clever Hans “got the right answer only when the questioner knew what the answer was, and the horse could see the questioner.” If the person asking the question knew the correct answer, Hans correctly answered the question 89% of the time, but when the person asking the question didn’t know the answer, Hans got it right only 6% of the time!

[Oskar] Pfungst then proceeded to examine the behaviour of the questioner in detail, and showed that as the horse’s taps approached the right answer, the questioner’s posture and facial expression changed in ways that were consistent with an increase in tension, which was released when the horse made the final, correct tap. This provided a cue that the horse could use to tell it to stop tapping.

Furthermore…

After Pfungst had become adept at giving Hans performances himself, and was fully aware of the subtle cues which made them possible, he discovered that he would produce these cues involuntarily regardless of whether he wished to exhibit or suppress them.

I love this story for so many reasons. First, when I heard it, I was consistently wrong in guessing what the trick was. I figured that the owner was intentionally communicating the answers to Hans. Then when I heard what was really happening, I started thinking about where else the Clever Hans Effect might happen. For example, a UC Davis study has shown that the handlers of drug sniffing dogs can influence their ability to spot drugs.

I believe that this is also happening in our classrooms. Going back to the beginning of this blog post, could it be that we are doing the same thing with our students? Sometimes I feel like we ask students questions and then stand there waiting for them to tap out the answers with their hooves. Rather than really thinking about what we’re asking, could it be that they’re just reading our body language and adjusting their answer until it appears that they answered it correctly? It sure seems that way when we get responses like “Yes… No… Uh… Yes…”

Thinking about how to mitigate this possibility, perhaps instead of practicing our poker face to prevent this from happening, we should instead be thinking about how to ask questions that Clever Hans could not answer. When we primarily ask yes/no questions or ones with numeric values, we set ourselves up for these situations.

I’ve found that most questions which begin with “How…?” or “Why.. ?” get kids talking about what they know and would be unanswerable by Clever Hans. It takes practice to incorporate them, and if you’re interested in some professional development tools to do so, check out these free questioning scenarios which allow you to practice questioning in trios using role-playing.

I always ask those 2 questions, otherwise it’s only about getting the “right “ answer and then the thinking stops. I enjoyed this!

Thanks Nick. How and Why sure are powerful.

I have often asked students, “Are you sure?” This almost always means the answer given was incorrect, in most classrooms. I ask it when students are correct AND incorrect. It leads them to rethink and justify their response – exactly what we want them to do!

Nice Susan. I like a variation of that question “How can we be sure you’re right?” or “How did you reach that answer?”. It avoids potential yes/no answers and goes straight to explanations.