- When will the winning Minecraft pickaxe finish?

Once the race starts the gold pickaxe takes an early lead, but the video ends about four seconds into the race so the ending isn’t clear. This is a great place to stop and ask students to make an estimate for how long it will take the winning pickaxe to finish the race.

If you’re not already using a Problem Solving Framework with your students, it has a section where they can list their low, high, and best estimate. For example, a student might pick 15 seconds for a low estimate (“It has to be at least 15 seconds!”), 60 seconds for a high estimate (“Even if it was reaaaaally slow, it’d have to be less than 60 seconds”), and 30 seconds for a best estimate. Students might decide to use the horizontal representation of the entire track at the top of the video to estimate what proportion of the race has already been completed by their preferred pickaxe.

The experience of having to make an estimate is likely to leave these spies deeply unsatisfied. They may say things like “How are we supposed to know how long it will take to finish when we don’t know ____________________?!” This is exactly where you want them because now they’re both interested in the context and ready to control how the problem solving continues.

They may ask for some or all of the following information, but only give them what they ask for. They need to learn what information they need.

What kind of block are the pickaxes breaking?

Stone blocks

How long is the track?

There are 134 blocks

How long does it take each pickaxe to break a block?

This table lists the number of seconds it takes for each pickaxe to break a stone block. There’s actually a mistake in the data that I would recommend saying nothing about and seeing if students discover it.

Both the gold and netherite pickaxes are listed as breaking a block in 0.25 seconds. That should seem suspicious considering the gold pickaxe seems to be faster. The correct value for gold should be 0.2 seconds. This also matches with the video where iron is always about halfway between the gold pickaxe and the start.

Depending on how familiar your students are with Minecraft, they may or may not ask this next question:

How long will each pickaxe last?

This is each pickaxe’s duability as measured by how many blocks it can break before it wears out and breaks. If they don’t ask for it, it’ll be an unexpected surprise that will come out later.

For example, students might say something like “If it takes iron 0.4 seconds to break a stone block and there are 134 stone blocks to break, then it should take about 53 seconds to finish the race.”

If students have limited experience with Minecraft, it would be reasonable to expect that gold will win. Unfortunately, they’re not considering another factor in Minecraft: durability. Items will break after a certain number of uses (in this case a use is breaking a block) and this race is long enough for several pickaxes to break and not finish!

To make sure everyone is on the same page about both the context (gold is going to break, not win) and their calculations, you can provide students with a checkpoint so they can see if they’re on the right track, make corrections if they’re not, and still have a chance to celebrate at the end if they’re right.

Say something like, “To make sure you’re all on the right track, I now want to show you the first half of the race. So figure out which pickaxe you think will be leading at the halfway point and how long it will take it to get there.” You can then play this video from them that ends at the halfway point in the race.

Remember that for some students, it may be entirely unexpected that gold is not going to win. Students might seem deflated at first, but this curveball will make the lesson more memorable and they’ll still have a chance to get back on track.

At this point, you’ll get lots of data about where students are at including:

Students don’t understand what the time represents

The timer is not in seconds and milliseconds but rather seconds and frames. While there are sixty seconds in a minute, there are only 30 frames in a second. So, 12:15 represents 12.5 seconds (because 15 frames is half of 30 frames), not 12.15 or 12.25 seconds.

Students might not have expected the gold pickaxe to break

If students ask you why you didn’t tell them some pickaxes would break, remind them that they never asked for that information. Then you can show them the durability chart above.

Students might wonder why their calculations don’t match the time

It’s a great opportunity to do some error analysis and ask them why they think that happened. For example, it could be anything from their calculations were incorrect or maybe it was something out of their control like the timers being slightly off. The discussion could turn to acceptable margins of error and how all races have some amount of rounding with the times.

Now give them time to continue working, revise their answers as needed, and come up with the exact time that the winning pickaxe will cross the finish line. They can also come up with times for the other pickaxes if desired.

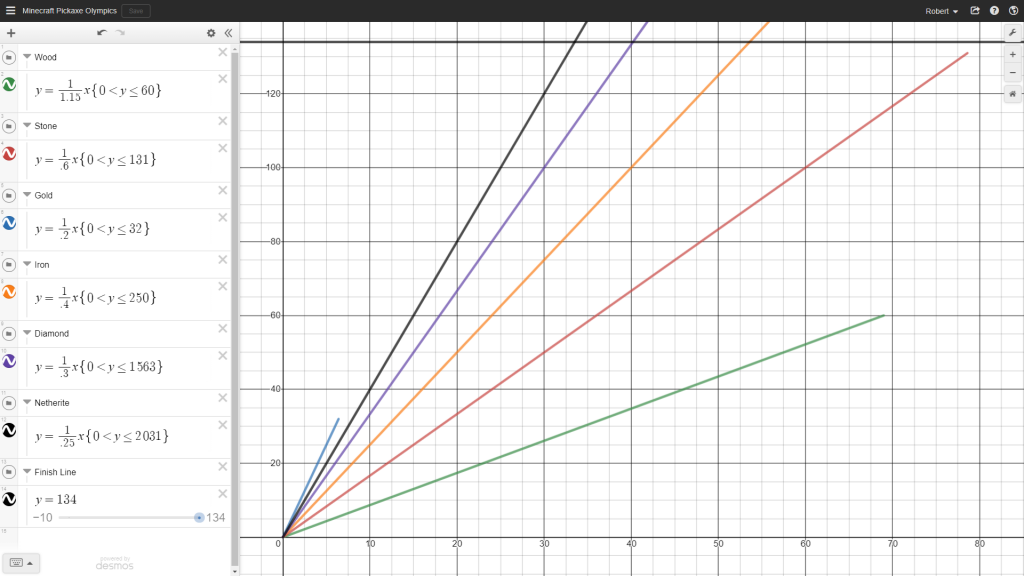

This problem also gives you an opportunity to discuss domain and range. Consider this Desmos graph below. It measures seconds on the x-axis and blocks broken on the y-axis. For example, the gold pickaxe (in blue) has the steepest slope because it breaks the most blocks per second. Note that gold’s range is 0 < y ≤ 32 because it breaks after the 32nd block broken. Also note that the slopes in the equations are one over the values in the table above (under "How long does it take each pickaxe to break a block?") because the table lists the speeds are seconds per block and we want them in blocks per second.

Ultimately, the actual finishing times for each pickaxe are:

- 1st – Netherite in 33.83 seconds (33.5 seconds expected time)

- 2nd – Diamond in 40.67 seconds (40.2 seconds expected time)

- 3rd – Iron in 54.27 seconds (53.6 seconds expected time)

- Did not finish – Stone broke after 131 blocks

- Did not finish – Wood broke after 60 blocks

- Did not finish – Gold broke after 32 blocks

- CCSS 6.RP.3b – Solve unit rate problems including those involving unit pricing and constant speed. For example, if it took 7 hours to mow 4 lawns, then at that rate, how many lawns could be mowed in 35 hours? At what rate were lawns being mowed?

- CCSS 7.RP.2 – Recognize and represent proportional relationships between quantities.

- CCSS F-IF.1 – Understand that a function from one set (called the domain) to another set (called the range) assigns to each element of the domain exactly one element of the range. If f is a function and x is an element of its domain, then f(x) denotes the output of f corresponding to the input x. The graph of f is the graph of the equation y = f(x).

This is exactly why nobody uses Golden pickaxes, THEY ARE SO WEAK

P.S. Rip stone pickaxe, you were so close lol

gold is very value why smaller than wooden pickaxe?

….. have you realized that the golden pickaxe’s duribility is absolutely horrendous? It can’t even mine iron, GOLD, diamonds, emeralds, redstone, lapis, or ancient debris (Netherite), therefore making it the most useless and terrible pickaxe in history. But gold is good for golden apples, but that’s pretty much it….

Well, gold pickaxes are good for clearing out large areas if you got gold and wood to burn. But, yeah, that’s pretty much it.

Gold in and of itself is not as useless as it was though, thanks to its use in the nether update.

How do you use this in your class? Is it an introduction to the content or more of an application? If it’s an intro, what have you discovered is the best way to debrief the activity and make sure they understood the content? Thanks for your thoughts. Great activity!

I think that this blog post will be helpful in unpacking how I use these kinds of lessons: https://robertkaplinsky.com/two-ways-integrate-problem-based-learning-unit-another-avoid/. I recommend Option Two, which is a bit like an introduction AND an application. In terms of the best way to debrief something like this, this book is the best strategy I have ever used: https://amzn.to/3KrP8qC.